19th Century Actor Autobiographies

By George Iles, Editor

Sir Henry Irving

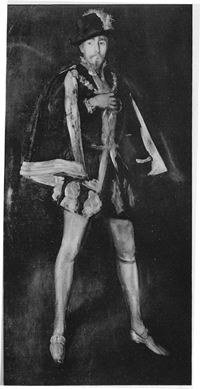

Painting, Arrangement in Black, No. 3: Sir Henry Irving as Philip II

of Spain (1876-1885), by James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), reproduced

as frontispiece in Henry Irving, The Drama: Addresses (London, 1893)

[On November 24, 1883, Henry Irving closed his first engagement in New York. William Winter’s review appeared next morning in the Tribune, It is reprinted in his book, “Henry Irving,” published by G. J. Coombes, New York, 1889. Mr. Winter said: “Mr. Irving has impersonated here nine different men, each one distinct from all the others. Yet in so doing he has never ceased to exert one and the same personal charm, the charm of genialised intellect. The soul that is within the man has suffused his art and made it victorious. The same forms of expression, lacking this spirit, would have lacked the triumph. All of them, indeed, are not equally fine. Mr. Irving’s ’Mathias’ and ’Louis XI,’ are higher performances than his ’Shylock’ and ’Dorincourt,’ higher in imaginative tone and in adequacy of feeling and treatment. But, throughout all these forms, the drift of his spirit, setting boldly away from conventions and formalities, has been manifested with delightful results. He has always seemed to be alive with the specific vitality of the person represented. He has never seemed a wooden puppet of the stage, bound in by formality and straining after a vague scholastic ideal of technical correctness.”

Mr. Irving’s addresses, “The Drama,” copyright by the United States Book Company, New York, were published in 1892. They furnish the pages now presented,–abounding on self-revelation,–ED.)

The Stage as an Instructor

To boast of being able to appreciate Shakespeare more in reading him than in seeing him acted used to be a common method of affecting special intellectuality. I hope this delusion–a gross and pitiful one to most of us–has almost absolutely died out. It certainly conferred a very cheap badge of superiority on those who entertained it. It seemed to each of them an inexpensive opportunity of worshipping himself on a pedestal. But what did it amount to? It was little more than a conceited and feather-headed assumption that an unprepared reader, whose mind is usually full of far other things, will see on the instant all that has been developed in hundreds of years by the members of a studious and enthusiastic profession. My own conviction is that there are few characters or passages of our great dramatists which will not repay original study. But at least we must recognise the vast advantages with which a practised actor, impregnated by the associations of his life, and by study–with all the practical and critical skill of his profession up to the date at which he appears, whether he adopts or rejects tradition–addresses himself to the interpretation of any great character, even if he have no originality whatever. There is something still more than this, however, in acting. Every one who has the smallest histrionic gift has a natural dramatic fertility; so that as soon as he knows the author’s text, and obtains self-possession, and feels at home in a part without being too familiar with it, the mere automatic action of rehearsing and playing it at once begins to place the author in new lights, and to give the personage being played an individuality partly independent of, and yet consistent with, and rendering more powerfully visible, the dramatist’s conception. It is the vast power a good actor has in this way which has led the French to speak of creating a part when they mean its first being played, and French authors are as conscious of the extent and value of this cooperation of actors with them, that they have never objected to the phrase, but, on the contrary, are uniformly lavish in their homage to the artists who have created on the boards the parts which they themselves have created on paper.

Inspiration in Acting

It is often supposed that great actors trust to the inspiration of the moment. Nothing can be more erroneous. There will, of course, be such moments, when an actor at a white heat illumines some passage with a flash of imagination (and this mental condition, by the way, is impossible to the student sitting in his armchair); but the great actor’s surprises are generally well weighed, studied, and balanced. We know that Edmund Kean constantly practised before a mirror effects which startled his audience by their apparent spontaneity. It is the accumulation of such effects which enables an actor, after many years, to present many great characters with remarkable completeness.

I do not want to overstate the case, or to appeal to anything that is not within common experience, so I can confidently ask you whether a scene in a great play has not been at some time vividly impressed on your minds by the delivery of a single line, or even of one forcible word. Has not this made the passage far more real and human to you than all the thought you have devoted to it? An accomplished critic has said that Shakespeare himself might have been surprised had he heard the “Fool, fool, fool!” of Edmund Kean. And though all actors are not Keans, they have in varying degree this power of making a dramatic character step out of the page, and come nearer to our hearts and our understandings.

After all, the best and most convincing exposition of the whole art of acting is given by Shakespeare himself: “To hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature, to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure." Thus the poet recognised the actor’s art as a most potent ally in the representations of human life. He believed that to hold the mirror up to nature was one of the worthiest functions in the sphere of labour, and actors are content to point to his definition of their work as the charter of their privileges.

Acting as an Art. How Irving Began

The practice of the art of acting is a subject difficult to treat with the necessary brevity. Beginners are naturally anxious to know what course they should pursue. In common with other actors, I receive letters from young people many of whom are very earnest in their ambition to adopt the dramatic calling, but not sufficiently alive to the fact that success does not depend on a few lessons in declamation. When I was a boy I had a habit which I think would be useful to all young students. Before going to see a play of Shakespeare’s I used to form–in a very juvenile way–a theory as to the working out of the whole drama, so as to correct my conceptions by those of the actors; and though I was, as a rule, absurdly wrong, there can be no doubt that any method of independent study is of enormous importance, not only to youngsters, but also to students of a larger growth. Without it the mind is apt to take its stamp from the first forcible impression it receives, and to fall into a servile dependence upon traditions, which, robbed of the spirit that created them, are apt to be purely mischievous. What was natural to the creator is often unnatural and lifeless in the imitator. No two people form the same conceptions of character, and therefore it is always advantageous to see an independent and courageous exposition of an original ideal. There can be no objection to the kind of training that imparts a knowledge of manners and customs, and the teaching which pertains to simple deportment on the stage is necessary and most useful; but you cannot possibly be taught any tradition of character, for that has no permanence. Nothing is more fleeting than any traditional method or impersonation. You may learn where a particular personage used to stand on the stage, or down which trap the ghost of Hamlet’s father vanished; but the soul of interpretation is lost, and it is this soul which the actor has to re-create for himself. It is not mere attitude or tone that has to be studied; you must be moved by the impulse of being; you must impersonate and not recite.

Feeling as a Reality or a Semblance

It is necessary to warn you against the theory expounded with brilliant ingenuity by Diderot that the actor never feels. When Macready played Virginius, after burying his beloved daughter, he confessed that his real experience gave a new force to his acting in the most pathetic situations of the play. Are we to suppose that this was a delusion, or that the sensibility of the man was a genuine aid to the actor? Bannister said of John Kemble that he was never pathetic because he had no children. Talma says that when deeply moved he found himself making a rapid and fugitive observation on the alternation of his voice, and on a certain spasmodic vibration which it contracted in tears. Has not the actor who can thus make his feelings a part of his art an advantage over the actor who never feels, but who makes his observations solely from the feelings of others? It is necessary to this art that the mind should have, as it were, a double consciousness, in which all the emotions proper to the occasion may have full swing, while the actor is all the time on the alert for every detail of his method. It may be that his playing will be more spirited one night than another. But the actor who combines the electric force of a strong personality with a mastery of the resources of his art must have a greater power over his audiences than the passionless actor who gives a most artistic simulation of the emotions he never experiences.

Gesture. Listening as an Art. Team-Play on the Stage

With regard to gesture, Shakespeare’s advice is all-embracing. “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action, with this special observance that you overstep not the modesty of nature.” And here comes the consideration of a very material part of the actor’s business–by-play. This is of the very essence of true art. It is more than anything else significant of the extent to which the actor has identified himself with the character he represents. Recall the scenes between Iago and Othello, and consider how the whole interest of the situation depends on the skill with which the gradual effect of the poisonous suspicion instilled into the Moor’s mind is depicted in look and tone, slight of themselves, but all contributing to the intensity of the situation. One of the greatest tests of an actor is his capacity for listening. By-play must be unobtrusive; the student should remember that the most minute expression attracts attention, that nothing is lost, that by-play is as mischievous when it is injudicious as it is effective when rightly conceived, and that while trifles make perfection, perfection is no trifle. This lesson was enjoined on me when I was a very young man by that remarkable actress, Charlotte Cushman. I remember that when she played Meg Merrilies I was cast for Henry Bertram, on the principle, seemingly, that an actor with no singing voice is admirably fitted for a singing part. It was my duty to give Meg Merrilies a piece of money, and I did it after the traditional fashion by handing her a large purse full of the coin of the realm, in the shape of broken crockery, which was generally used in financial transactions on the stage, because when the virtuous maid rejected with scorn the advances of the lordly libertine, and threw his pernicious bribe upon the ground, the clatter of the broken crockery suggested fabulous wealth. But after the play Miss Cushman, in the course of some kindly advice, said to me: “Instead of giving me that purse, don’t you think it would have been much more natural if you had taken a number of coins from your pocket, and given me the smallest? That is the way one gives alms to a beggar, and it would have added to the realism of the scene.” I have never forgotten that lesson, for simple as it was, it contained many elements of dramatic truth. It is most important that an actor should learn that he is a figure in a picture, and that the least exaggeration destroys the harmony of the composition. All the members of the company should work toward a common end, with the nicest subordination of their individuality to the general purpose. Without this method a play when acted is at best a disjoined and incoherent piece of work, instead of being a harmonious whole like the fine performance of an orchestral symphony.

Continue...

Continue...![[Buy at Amazon]](http://images.amazon.com/images/P/0743292545.01.MZZZZZZZ.jpg)