The Nature of Goodness

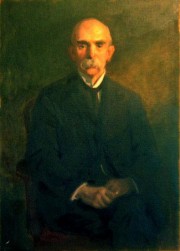

by George Herbert Palmer

George Herbert Palmer, (1842-1933)

Professor of Natural Religion, Moral Philosophy and Civil Polity

Harvard University

Portrait: 1926, 40 x 30 inches, Oil

II. Misconceptions of Goodness

I

Our diagram of goodness, as drawn in the last chapter, has its special imperfections, and through these cannot fail to suggest certain erroneous notions of goodness. To these I now turn. The first of them is connected with its own method of construction. It will be remembered that we arbitrarily threw an arrow from D to A, thus making what was hitherto an end become a means to its own means. Was this legitimate? Does any such closed circle exist?

It certainly does not. Our universe contains nothing that can be represented by that figure. Indeed if anywhere such a self-sufficing organism did exist, we could never know it. For, by the hypothesis, it would be altogether adequate to itself and without relations beyond its own bounds. And if it were thus cut off from connection with everything except itself, it could not even affect our knowledge. It would be a closed universe within our universe, and be for us as good as zero. We must own, then, that we have no acquaintance with any such perfect organism, while the facts of life reveal conditions widely unlike those here represented.

What these conditions are becomes apparent when we put significance into the letters hitherto employed. Let our diagram become a picture of the organic life of John. Then A might represent his physical life, B his business life, C his civil, D his domestic; and we should have asserted that each of these several functions in the life of John assists all the rest. His physical health favors his commercial and political success, while at the same time making him more valuable in the domestic circle. But home life, civic eminence, and business prosperity also tend to confirm his health. In short, every one of these factors in the life of John mutually affects and is affected by all the others.

But when thus supplied with meaning, Figure 3 evidently fails to express all it should say. B is intended to exhibit the business life of John. But this is surely not lived alone. Though called a function of John, it is rather a function of the community, and he merely shares it. I had no right to confine to John himself that which plainly stretches beyond him. Let us correct the figure, then, by laying off another beside it to represent Peter, one of those who shares in the business experience of John. This common business life

of theirs, B, we may say, enables Peter to gratify his own adventurous disposition, E; and this again stimulates his scientific tastes, F. But Peter’s eminence in science commends him so to his townsmen that he comes to share again C, the civic life of John. Yet as before in the case of John, each of Peter’s powers works forward, backward, and across, constructing in Peter an organic whole which still is interlocked with the life of John. Each, while having functions of his own, has also functions which are shared with his neighbor.

Nor would this involvement of functions pause with Peter. To make our diagram really representative, each of the two individuals thus far drawn would need to be surrounded by a multitude of others, all sharing in some degree the functions of their neighbors. Or rather each individual, once connected with his neighbors, would find all his functions affected by all those possessed by his entire group. For fear of making my figure unintelligible through its fullness of relations, I have sent out arrows in all directions from the letter A only; but in reality they would run from all to all. And I have also thought that we persons affect one another quite as decidedly through the wholeness of our characters as we do through any interlocking of single traits. Such totality of relationship I have tried to suggest by connecting the centres of each little square with the centres of adjacent ones. John as a whole is thus shown to be good for Peter as a whole.

We have successively found ourselves obliged to broaden our conception until the goodness of a single object has come to imply that of a group. The two phases of goodness are thus seen to be mutually dependent. Extrinsic goodness or serviceability, that where an object employs an already constituted wholeness to further the wholeness of another, cannot proceed except through intrinsic goodness, or that where fullness and adjustment of functions are expressed in the construction of an organism. Nor can intrinsic goodness be supposed to exist shut up to itself and parted from extrinsic influence. The two are merely different modes or points of view for assessing goodness everywhere. Goodness in its most elementary form appears where one object is connected with another as means to end. But the more elaborately complicated the relation becomes, and the richer the entanglement of means and ends–internal and external–in the adjustment of object or person, so much ampler is the goodness. Each object, in order to possess any good, must share in that of the universe.

II

But the diagram suggests a second question. Are all the functions here represented equally influential in forming the organism? Our figure implies that they are, and I see no way of drawing it so as to avoid the implication. But it is an error. In nature our powers have different degrees of influence. We cannot suppose that John’s physical, commercial, domestic, and political life will have precisely equal weight in the formation of his being. One or the other of them will play a larger part. Accordingly we very properly speak of greater goods and lesser goods, meaning by the former those which are more largely contributory to the organism. In our physical being, for example, we may inquire whether sight or digestion is the greater good; and our only means of arriving at an answer would be to stop each function and then note the comparative consequence to the organism. Without digestion, life ceases; without sight, it is rendered uncomfortable. If we are considering merely the relative amounts of bodily gain from the two functions, we must call digestion the greater good. In a table, excellence of make is apt to be a greater good than excellence of material, the character of the carpentry having more effect on its durability than does the special kind of wood employed. The very doubts about such results which arise in certain cases confirm the truth of the definition here proposed; for when we hesitate, it is on account of the difficulty we find in determining how far maintenance of the organism depends on the one or the other of the qualities compared. The meaning of the terms greater and lesser is clearer than their application. A function or quality is counted a greater good in proportion as it is believed to be more completely of the nature of a means.

III

Another question unsettled by the diagram is so closely connected with the one just examined as often to be confused with it. It is this: Are all functions of the same kind, rank, or grade? They are not; and this qualitative difference is indicated by the terms higher and lower, as the quantitative difference was by greater and less. But differences of rank are more slippery matters than difference of amount, and easily lend themselves to arbitrary and capricious treatment. In ordinary speech we are apt to employ the words high and low as mere signs of approval or disapproval. We talk of one occupation, enjoyment, work of art, as superior to another, and mean hardly more than that we like it better. Probably there is not another pair of terms current in ethics where the laudatory usage is so liable to slip into the place of the descriptive. Our opponent’s ethics always seem to embody low ideals, our own to be of a higher type. Accordingly the terms should not be used in controversy unless we have in mind for them a precise meaning other than eulogy or disparagement.

And such a meaning they certainly may possess. As the term greater good is employed to indicate the degree in which a quality serves as a means, so may the higher good show the degree in which it is an end. Digestion, which was just now counted a greater good than sight, might still be rightly reckoned a lower; for while it contributes more largely to the constitution of the human organism, it on that very account expresses less the purposes to which that organism will be put. It is true we have seen how in any organism every power is both means and end. It would be impossible, then, to part out its powers, and call some altogether great and others altogether high. But though there is purpose in all, and construction in all, certain are more markedly the one than the other. Some express the superintending functions; others, the subservient. Some condition, others are conditioned by. In man, for example, the intellectual powers certainly serve our bodily needs. But that is not their principal office; rather, in them the aims of the entire human being receive expression. To abolish the distinction of high and low would be to try to obliterate from our understanding of the world all estimates of the comparative worth of its parts; and with these estimates its rational order would also disappear. Such attempts have often been made. In extreme polytheism there are no superiors among the gods and no inferiors, and chaos consequently reigns. A similar chaos is projected into life when, as in the poetry of Walt Whitman, all grades of importance are stripped from the powers of man and each is ranked as of equal dignity with every other.

That there is difficulty in applying the distinction, and determining which function is high and which low, is evident. To fix the purposes of an object would often be presumptuous. With such perplexities I am not concerned. I merely wish to point out a perfectly legitimate and even important signification of the terms high and low, quite apart from their popular employment as laudatory or depreciative epithets. It surely is not amiss to call the legibility of a book a higher good than its shape, size, or weight, though in each of these some quality of the book is expressed.

IV

A further point of possible misconception in our diagram is the number of factors represented. As here shown, these are but four. They might better be forty. The more richly functional a thing or person is, the greater its goodness. Poverty of powers is everywhere a form of evil. For how can there be largeness of organization where there is little to organize? Or what is the use of organization except as a mode of furnishing the smoothest and most compact expression to powers? Wealth and order are accordingly everywhere the double traits of goodness, and a chief test of the worth of any organism will be the diversity of the powers it includes. Throughout my discussion I have tried to help the reader to keep this twofold goodness in mind by the use of such phrases as “fullness of organization.”

Yet it must be confessed that between the two elements of goodness there is a kind of opposition, needful though both are for each other. Order has in it much that is repressive; and wealth–in the sense of fecundity of powers–is, especially at its beginning, apt to be disorderly. When a new power springs into being, it is usually chaotic or rebellious. It has something else to attend to besides bringing itself into accord with what already exists. There is violence in it, a lack of sobriety, and only by degrees does it find its place in the scheme of things. This is most observable in living beings, because it is chiefly they who acquire new powers. But there are traces of it even among things. A chemical acid and base meeting, are pretty careless of everything except the attainment of their own action. Human beings are born, and for some time remain, clamorous, obliging the world around to attend more to them than they to it. There is ever a confusion in exuberant life which bewilders the onlooker, even while he admits that life had better be.

The deep opposition between these contrasted sides of goodness is mirrored in the conflicting moral ideals of conservatism and radicalism, of socialism and individualism, which have never been absent from the societies of men, nor even, I believe, from those of animals. Conservatism insists on unity and order; radicalism on wealthy life, diversified powers, particular independence. Either, left to itself, would crush society, one by emptying it of initiative, the other by splitting it into a company of warring atoms. Ordinarily each is dimly aware of its need of an opponent, yet does not on that account denounce him the less, or less eagerly struggle to expel him from provinces asserted to be its own.

By temperament certain classes of the community are naturally disposed to become champions of the one or the other of these supplemental ideals. Artists, for the most part, incline to the ideal of abounding life, exult in each novel manifestation which it can be made to assume, and scoff at order as Philistinism.

Moralists, on the other hand, lay grievous stress on order, as if it had any value apart from its promotion of life. Assuming that sufficient exuberance will come, unfostered by morality, they shut it out from their charge, make duty to consist in checking instinct, and devote themselves to pruning the sprouting man. But this is absurdly to narrow ethics, whose true aim is to trace the laws involved in the construction of a good person. In such construction the supply of moral material, and the fostering of a wide diversity of vigorous powers, is as necessary as bringing these powers into proper working form. Richness of character is as important as correctness. The world’s benefactors have often been one-sided and faulty men. None of us can be complete; and we had better not be much disturbed over the fact, but rather set ourselves to grow strong enough to carry off our defects.

Because ethics has not always kept its eyes open to this obvious duality of goodness it has often incurred the contempt of practical men. The ethical writers of our time have done better. They have come to see that the goodness of a person or thing consists in its being as richly diversified as is possible up to the limit of harmonious, working, and also in being orderly up to the limit of repression of powers. Beyond either of these limits evil begins. What I have expressed in my diagram as the fullest organization is intended to lie within them.

V

It remains to compare the view of goodness here presented with two others which have met with wide approval. The competence of my own will be tested by seeing whether it can explain these, or they it. Goodness is sometimes defined as that which satisfies desire. Things are not good in themselves, but only as they respond to human wishes. A certain combination of colors or sounds is good, because I like it. A republic we Americans consider the best form of government because we believe that this more completely than any other meets the legitimate desires of its people. I know a little boy who after tasting with gusto his morning’s oatmeal would turn for sympathy to each other person at table with the assertive inquiry, “Good? Good? Good?” He knew no good but enjoyment, and this was so keen that he expected to find it repeated in each of his friends. It is true we often call actions good which are not immediately pleasing; for example, the cutting off of a leg which is crushed past the possibility of cure. But the leg, if left, will cause still more distress or even death. In the last analysis the word good will be found everywhere to refer to some satisfaction of human desire. If we count afflictions good, it is because we believe that through them permanent peace may best be reached. And rightly do those name the Bible the Good Book who think that it more than any other has helped to alleviate the woes of man.

With this definition I shall not quarrel. So far as it goes, it seems to me not incorrect. In all good I too find satisfaction of desire. Only, though true, the definition is in my judgment vague and inadequate. For we shall still need some standard to test the goodness of desires. They themselves may be good, and some of them are better than others. It is good to eat candy, to love a friend, to hate a foe, to hear the sound of running water, to practice medicine, to gather wealth, learning, or postage stamps. But though each of these represents a natural desire, they cannot all be counted equally good. They must be tried by some standard other than themselves. For desires are not detachable facts. Each is significant only as a piece of a life. In connection with that life it must be judged. And when we ask if any desire is good or bad, we really inquire how far it may play a part in company with other desires in making up a harmonious existence. By its organic quality, accordingly, we must ultimately determine the goodness of whatever we desire. If it is organic, it certainly will satisfy desire. But we cannot reverse this statement and assert that whatever satisfies desire will be organically good. My own mode of statement is, therefore, clearer and more adequate than the one here examined, because it brings out fully important considerations which in this are only implied. Whatever contributes to the solidity and wealth of an organism is, from the point of view of that organism, good.

VI

A second inadequate definition of goodness is that it is adaptation to environment. This is a far more important conception than the preceding; but again, while not untrue, is still, in my judgment, partial and ambiguous. When its meaning is made clear and exact, it seems to coincide with my own; for it points out that nothing can be separately good, but becomes so through fulfillment of relations. Each thing or person is surrounded by many others. To them it must fit itself. Being but a part, its goodness is found in serving that whole with which it is connected. That is a good oar which suits well the hands of the rower, the row-lock of the boat, and the resisting water. The white fur of the polar bear, the tawny hide of the lion, the camel’s hump, giraffe’s neck, and the light feet of the antelope, are all alike good because they adapt these creatures to their special conditions of existence and thus favor their survival. Nor is there a different standard for moral man. His actions which are accounted good are called so because they are those through which he is adapted to his surroundings, fitted for the society of his fellows, and adjusted with the best chance of survival to his encompassing physical world.

While I have warm approval for much that appears in such a doctrine, I think those who accept it may easily overlook certain important elements of goodness. At best it is a description of extrinsic goodness, for it separates the object from its environment and makes the response of the former to an external call the measure of its worth. Of that inner worth, or intrinsic goodness, where fullness and adjustment of relations go on within and not without, it says nothing. Yet I have shown how impossible it is to conceive one of these kinds of goodness without the other.

But a graver objection still–or rather the same objection pressed more closely–is this. The present definition naturally brings up the picture of certain constant and stable surroundings enclosing an environed object which is to be changed at their demand. No such state of things exists. There is no fixed environment. It is always fixable. Every environment is plastic and derives its character, at least partially, from the environed object. Each stone sends out its little gravitative and chemical influence upon surrounding stones, and they are different through being in its neighborhood. The two become mutually affected, and it is no more suitable to say that the object must adapt itself to its environment than that the environment must be adapted to its object.

Indeed, in persons this second form of statement is the more important; for the forcing of circumstances into accordance with human needs may be said to be the chief business of human life. The man who adapts himself to his ignorant, licentious, or malarial surroundings, is not a type of the good man. Of course disregard of environment is not good either. Circumstances have their honorable powers, and these require to be studied, respected, and employed. Sometimes they are so strong as to leave a person no other course than to adapt himself to them. He cannot adapt them to himself. Plato has a good story of how a native of the little village of Seriphus tried to explain Themistocles by means of environment. “You would not,” he said to the great man, “have been eminent if you had been born in Seriphus.” “Probably not," answered Themistocles, “nor you, if you had been born in Athens.”

The definition we are discussing, then, is not true–indeed it is hardly intelligible–if we take it in the one-sided way in which it is usually announced. The demand for adaptation does not proceed exclusively from environment, surroundings, circumstance. The stone, the tree, the man, conforms these to itself as truly as it is conformed to them. There is mutual adaptation. Undoubtedly this is implied in the definition, and the petty employment of it which I have been attacking would be rejected also by its wiser defenders. But when its meaning is thus filled out, its vagueness rendered clear, and the mutual influence which is implied becomes clearly announced, the definition turns into the one which I have offered. Goodness is the expression of the largest organization. Its aim is everywhere to bring object and environment into fullest cooperation. We have seen how in any organic relationship every part is both means and end. Goodness tends toward organism; and so far as it obtains, each member of the universe receives its own appropriate expansion and dignity. The present definition merely states the great truth of organization with too objective an emphasis; as that which found the satisfaction of desire to be the ground of goodness over-emphasized the subjective side. The one is too legal, the other too aesthetic. Yet each calls attention to an important and supplementary factor in the formation of goodness.

VII

In closing these dull defining chapters, in which I have tried to sum up the notion of goodness in general–a conception so thin and empty that it is equally applicable to things and persons–it may be well to gather together in a single group the several definitions we have reached.

Intrinsic goodness expresses the fulfillment of function in the construction of an organism.

By an organism is meant such an assemblage of active and differing parts that in it each part both aids and is aided by all the others.

Extrinsic goodness is found when an object employs an already constituted wholeness to further the wholeness of others.

A part is good when it furnishes that and that only which may add value to other parts.

A greater good is one more largely contributory to the organism as its end.

A higher good is one more fully expressive of that end.

Probably, too, it will be found convenient to set down here a couple of other definitions which will hereafter be explained and employed. A good act is the expression of selfhood as service. By an ideal we mean a mental picture of a better state of existence than we feel has actually been reached.

REFERENCES ON MISCONCEPTIONS OF GOODNESS

Alexander’s Moral Order and Progress, bk. iii. ch. i. Section 10.

Martineau’s Types of Ethical Theory, vol. ii. bk. i. ch. i. Section 2.

Mackenzie’s Manual of Ethics, ch. v. Section 13 & ch. vii. Section 2.

Janet’s Theory of Morals, ch. iii.

Dewey’s Outlines of Ethics, Section lxvii.

Spencer’s Principles of Ethics, pt. i. ch. 3.

Continue...

Continue...![[Buy at Amazon]](http://images.amazon.com/images/P/0766150887.01.MZZZZZZZ.jpg)