The Nature of Goodness

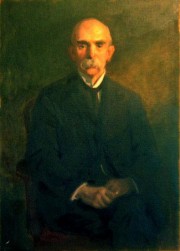

by George Herbert Palmer

George Herbert Palmer, (1842-1933)

Professor of Natural Religion, Moral Philosophy and Civil Polity

Harvard University

Portrait: 1926, 40 x 30 inches, Oil

VII. The Three Stages of Goodness

I

Such is the mighty argument conducted through several centuries in behalf of nature against spirit as a director of conduct. I have stated it at length both because of its own importance and because it is in seeming conflict with the results of my early chapters. But those results stand fast. They were reached with care. To reject them would be to obliterate all distinction between persons and things. Self-consciousness is the indisputable prerogative of persons. Only so far as we possess it and apply it in action do we rise above the impersonal world around. And even if we admit the contention in behalf of nature as substantially sound, we are not obliged to accept it as complete. It may be that neither nature nor spirit can be dispensed with in the supply of human needs. Each may have its characteristic office; for though in the last chapter I have been setting forth the superiorities of natural guidance, in spiritual guidance there are advantages too, advantages of an even more fundamental kind. Let us see what they are.

They may be summarily stated in a single sentence: consciousness alone gives fresh initiative. Disturbing as the influence of consciousness confessedly is, on its employment depends every possibility of progress. Natural action is regular, constant, conformed to a pattern. In the natural world event follows event in a fixed order, Under the same conditions the same result appears an indefinite number of times. The most objectionable form of this rigidity is found in mechanism. I sometimes hear ladies talking about “real lace” and am on such occasions inclined to speak of my real boots. They mean, I find, not lace that is the reverse of ghostly, but simply that which bears the impress of personality. It is lace which is made by hand and shows the marks of hand work. Little irregularities are in it, contrasting it with the machine sort, where every piece is identical with every other piece. It might be more accurately called personal lace. The machine kind is no less real–unfortunately–but mechanism is hopelessly dull, says the same thing day after day, and never can say anything else.

Now though this coarse form of monotonous process nowhere appears in what we call the world of nature, a restriction substantially similar does; for natural objects vary slowly and within the narrowest limits. Outside such orderly variations, they are subjected to external and distorting agencies effecting changes in them regardless of their gains. Branches of trees have their wayward and subtle curvatures, and are anything but mechanical in outline. But none the less are they helpless, unprogressive, and incapable of learning. The forces which play upon them, being various, leave a truly varied record. But each of these forces was an invariable one, and their several influences cannot be sorted, judged, and selected by the tree with reference to its future growth. Criticism and choice have no place here, and accordingly anything like improvement from year to year is impossible.

The case of us human beings would be the same if we were altogether managed by the sure, swift, and easy forces of nature. Progress would cease. We should move on our humdrum round as fixedly constituted, as submissive to external influence, and with as little exertion of intelligence as the dumb objects we behold. Every power within us would be actual, displayed in its full extent, and involving no variety of future possibility. We should live altogether in the present, and no changes would be imagined or sought. From this dull routine we are saved by the admixture of consciousness. For a gain so great we may well be ready to encounter those difficulties of conscious guidance which my last chapter detailed. Let the process of advance be inaccurate, slow, and severe, so only there be advance. For progress no cost is too great. I am sometimes inclined to congratulate those who are acute sufferers through self-consciousness, because to them the door of the future is open. The instinctive, uncritical person, who takes life about as it comes, and with ready acceptance responds promptly to every suggestion that calls, may be as popular as the sunshine, but he is as incapable of further advance. Except in attractiveness, such a one is usually in later life about what he was in youth; for progress is a product of forecasting intelligence. When any new creation is to be introduced, only consciousness can prepare its path.

Evidently, then, there are strong advantages in guidance through the spirit. But natural guidance has advantages no less genuine. Human life is a complex and demanding affair, requiring for its ever- enlarging good whatever strength can be summoned from every side. Probably we must abandon that magnificent conception of our ancestors, that spirit is all in all and nature unimportant. But must we, in deference to the temper of our time, eliminate conscious guidance altogether? May not the disparagement of recent ages have arisen in reaction against attempts to push conscious guidance into regions where it is unsuitable? Conceivably the two agencies may be supplementary. Possibly we may call on our fellow of the natural world for aid in spiritual work. The complete ideal, at any rate, of good conduct unites the swiftness, certainty, and ease of natural action with the selective progressiveness of spiritual. Till such a combination is found, either conduct will be insignificant or great distress of self-consciousness will be incurred. Both of these evils will be avoided if nature can be persuaded to do the work which we clearly intend. That is what goodness calls on us to effect. To showing the steps through which it may be reached the remainder of this chapter will be given.

II

Let us, then, take a case of action where we are trying to create a new power, to develop ourselves in some direction in which we have not hitherto gone. For such an undertaking consciousness is needed, but let us see how far we are able to hand over its work to unconsciousness. Suppose, when entirely ignorant of music, I decide to learn to play the piano. Evidently it will require the minutest watchfulness. Approaching the strange instrument with some uneasiness, I try to secure exactly that position on the stool which will allow my arms their proper range along the keyboard. There is difficulty in getting my sheet of music to stand as it should. When it is adjusted, I examine it anxiously. What is that little mark? Probably the note C. Among these curious keys there must also be a C. I look up and down. There it is! But can I bring my finger down upon it at just the right angle? That is accomplished, and gradually note after note is captured, until I have conquered the entire score. If now during my laborious performance a friend enters the room, he might well say, “I do not like spiritual music. Give me the natural kind which is not consciously directed.” But let him return three years later. He will find me sitting at the piano quite at my ease, tossing off notes by the unregarded handful. He approaches and enters into conversation with me. I do not cease my playing; but as I talk, I still keep my mind free enough to observe the swaying boughs outside the window and to enjoy the fragrance of the flowers which my friend has brought. The musical phrases which drop from my fingers appear to regulate themselves and to call for little conscious regard.

Yet if my friend should try to show me how mistaken I had been in the past, attempting to manage consciously what should have been left to nature, if he should eulogize my natural action now and contrast it with my former awkwardness, he would plainly be in error. My present naturalness is the result of long spiritual endeavor, and cannot be had on cheaper terms; and the unconsciousness which is now noticeable in me is not the same thing as that which was with me when I began to play. It is true the incidental hardships connected with my first attack on the piano have ceased. I find myself in possession of a new and seemingly unconscious power. An automatic train of movements has been constructed which I now direct as a whole, its parts no longer requiring special volitional prompting. But I still direct it, only that a larger unit has been constituted for consciousness to act upon. The naturalness which thus becomes possible is accordingly of an altogether new sort; and since the result is a completer expression of conscious intention, it may as truly be called spiritual as natural.

III

It has now become plain that our early reckoning of actions as either natural or spiritual was too simple and incomplete. Conduct has three stages, not two. Let us get them clearly in mind. At the beginning of life we are at the beck and call of every impulse, not having yet attained reflective command of ourselves. This first stage we may rightly call that of nature or of unconsciousness, and manifestly most of us continue in it to some extent and as regards certain tracts of action throughout life. Then reflection is aroused; we become aware of what we are doing. The many details of each act and the relations which surround it come separately into conscious attention for assessment, approval, or rejection. This is the stage of spirit, or consciousness. But it is not the final stage. As we have seen in our example, a stage is possible when action runs swiftly to its intended end, but with little need of conscious supervision. This mechanized, purposeful action presents conduct in its third stage, that of second nature or negative consciousness. As this third is least understood, is often confused with the first, and yet is in reality the complete expression of the moral ideal and of that reconciliation of nature and spirit of which we are in search, I will devote a few pages to its explanation.

The phrase negative consciousness describes its character most exactly, though the meaning is not at once apparent. Positive consciousness marks the second stage. There we are obliged to think of each point involved, in order to bring it into action. In piano- playing, for example, I had to study my seat at the piano, the music on the rack, the letters of the keyboard, the position of my fingers, and the coordination of all these with one another. To each such matter a separate and positive attention is given. But even at the last, when I am playing at my ease, we cannot say that consciousness is altogether absent. I am conscious of the harmony, and if I do not direct, I still verify results. As an entire phrase of music rolls off my rapid fingers, I judge it to be good. But if one of the notes sticks, or I perceive that the phrase might be improved by a slightly changed stress, I can check my spontaneous movements and correct the error. There is therefore a watchful, if not a prompting, consciousness at work. It is true that, the first note started, all the others follow of themselves in natural sequence. Though I withdraw attention from my fingers, they run their round as a part of the associated train. But if they go awry, consciousness is ready with its inhibition. I accordingly call this the stage of negative consciousness. In it consciousness is not employed as a positive guiding force, but the moment inhibition or check is required for reaching the intended result, consciousness is ready and asserts itself in the way of forbiddal. This third stage, therefore, differs from the first through having its results embody a conscious purpose; from the second, through having consciousness superintend the process in a negative and hindering, rather than in a positive and prompting way. It is the stage of habit. I call it second nature because it is worked, not by original instincts, but by a new kind of associative mechanism which must first be laboriously constructed.

Years ago when I began to teach at Harvard College, we used to regard our students as roaring animals, likely to destroy whatever came in their way. We instructors were warned to keep the doors of our lecture rooms barred. As we came out, we must never fail to lock them. So always in going to a lecture, as I passed through the stone entry and approached the door my hand sought my pocket, the key came out, was inserted in the keyhole, turned, was withdrawn, fell back into my pocket, and I entered the room. This series of acts repeated day after day had become so mechanized that if on entering the room I had been asked whether on that particular day I had really unlocked the door, I could not have told. The train took care of itself and I was not concerned in it sufficiently for remembrance. Yet it remained my act. On one or two occasions, after shoving in the key in my usual unconscious fashion, I heard voices in the room and knew that it would be inappropriate to enter. Instantly I stopped and checked the remainder of the train. Habitual though the series of actions was, and ordinarily executed without conscious guidance, it as a whole was aimed at a definite end. If this were unattainable, the train stopped.

All are aware how large a part is played by such mechanization of conduct. Without it, life could not go on. When a man walks to the door, he does not decide where to set his foot, what shall be the length of his step, how he shall maintain his balance on the foot that is down while the other is raised. These matters were decided when he was a child. In those infant years which seem to us intellectually so stationary, a human being is probably making as large acquisitions as at any period of his later life. He is testing alternatives and organizing experience into ordered trains. But in the rest of us a consolidation substantially similar should be going on in some section of our experience as long as we live. For this is the way we develop: not the total man at once, but this year one tract of conduct is surveyed, judged, mechanized; and next year another goes through the same maturing process. Not until such mechanization has been accomplished is the conduct truly ours. When, for example, I am winning the power of speech, I gradually cease to study exactly the word I utter, the tone in which it is enunciated, how my tongue, lips, and teeth shall be adjusted in reference to one another. While occupied with these things, I am no speaker. I become such only when, the moment I think of a word, the actions needed for its utterance set themselves in motion. With them I have only a negative concern. Indeed, as we grow maturer of speech, collocations of words stick naturally together and offer themselves to our service. When we require a certain range of words from which to draw our means of communication, there they stand ready. We have no need to rummage the dimness of the past for them. Mechanically they are prepared for our service.

Of course this does not imply that at one period we foolishly believed consciousness to be an important guide, but subsequently becoming wiser, discarded its aid. On the contrary, the mechanization of second nature is simply a mode of extending the influence of consciousness more widely. The conclusions of our early lectures were sound. The more fully expressive conduct can be of a self-conscious personality, so much the more will it deserve to be called good. But in order that it may in any wide extent receive this impress of personal life, we must summon to our aid agencies other than spiritual. The more we mechanize conduct the better. That is what maturing ourselves means. When we say that a man has acquired character, we mean that he has consciously surveyed certain large tracts of life, and has decided what in those regions it is best to do. There, at least, he will no longer need to deliberate about action. As soon as a case from this region presents itself, some electric button in his moral organism is touched, and the whole mechanism runs off in the surest, swiftest, easiest possible way. Thus his consciousness is set free to busy itself with other affairs. For in this third stage we do not so much abandon consciousness as direct it upon larger units; and this not because smaller units do not deserve attention, but because they have been already attended to. Once having decided what is our best mode of action in regard to them, we wisely turn them over to mechanical control.

IV

Such is the nature of moral habit. Before goodness can reach excellence, it must be rendered habitual. Consideration, the mark of the second stage, disappears in the third. We cannot count a person honest so long as he has to decide on each occasion whether to take advantage of his neighbor. Long ago he should have disciplined himself into machine-like action as regards these matters, so that the dishonest opportunity would be instinctively and instantly dismissed, the honest deed appearing spontaneously. That man has not an amiable character who is obliged to restrain his irritation, and through all excitement and inner rage curbs himself courageously. Not until conduct is spontaneous, rooted in a second nature, does it indicate the character of him from whom it proceeds.

That unconsciousness is necessary for the highest goodness is a cardinal principle in the teaching of Jesus. Other teachers of his nation undertook clearly to survey the entirety of human life, to classify its situations and coolly to decide the amount of good and evil contained in each. Righteousness according to the Pharisees was found in conscious conformity to these decisions. Theirs was the method of casuistry, the method of minute, critical, and instructed judgment. The fields of morality and the law were practically identified, goodness becoming externalized and regarded as everywhere substantially the same for one man as for another. Pharisaism, in short, stuck in the second stage. Jesus emphasized the unconscious and subjective factor. He denounced the considerate conduct of the Pharisees as not righteousness at all. It was mere will-worship. Jesus preached a religion of the heart, and taught that righteousness must become an individual passion, similar to the passions of hunger and thirst, if it would attain to any worth. So long as evil is easy and natural for us, and good difficult, we are evil. We must be born again. We must attain a new nature. Our right hand must not know what our left hand does. We must become as little children, if we would enter into the kingdom of heaven.

The chief difficulty in comprehending this doctrine of the three stages lies in the easy confusion of the first and the third. Jesus guards against this, not bidding us to be or to remain children, but to become such. The unconsciousness and simplicity of childhood is the goal, not the starting-point. The unconsciousness aimed at is not of the same kind as that with which we set out. In early life we catch the habits of our home or even derive our conduct from hereditary bias. We begin, therefore, as purely natural creatures, not asking whether the ways we use are the best. Those ways are already fixed in the usages of speech, the etiquettes of society, the laws of our country. These things make up the uncriticised warp and woof of our lives, often admirably beautiful lives. When speaking in my last chapter of the way in which our age has come to eulogize guidance by natural conditions, I might have cited as a striking illustration the prevalent worship of childhood. Only within the last century has the child cut much of a figure in literature. He is an important enough figure to-day, both in and out of books. In him nature is displayed within the spiritual field, nature with the possibilities of spirit, but those possibilities not yet realized. We accordingly reverence the child and delight to watch him. How charming he is, graceful in movement, swift of speech, picturesque in action! Enviable little being! The more so because he is able to retain his perfection for so brief a time.

But we all know the unhappy period from seven to fourteen when he who formerly was all grace and spontaneity discovers that he has too many arms and legs. How disagreeable the boy then becomes! Before, we liked to see him playing about the room. Now we ask why he is allowed to remain. For he is a ceaseless disturber; constantly noisy and constantly aware of making a noise, his excuses are as bad as his indiscretions. He cannot speak without making some awkward blunder. He is forever asking questions without knowing what to do with the answers. A confused and confusing creature! We say he has grown backward. Where before he was all that is estimable, he has become all that we do not wish him to be.

All that we do not wish him to be, but certainly much more what God wishes him to be. For if we could get rid of our sense of annoyance, we should see that he is here reaching a higher stage, coming into his heritage and obtaining a life of his own. Formerly he lived merely the life of those about him. He laid a self-conscious grasp on nothing of his own. When now at length he does lay that grasp, we must permit him to be awkward, and to us disagreeable. We should aid him through the inaccurate, slow, and fatiguing period of his existence until, having tested many tracts of life and learned in them how to mechanize desirable conduct, he comes back on their farther side to a childhood more beautiful than the original. Many a man and woman possesses this disciplined childhood through life. Goodness seems the very atmosphere they breathe, and everything they do to be exactly fitting. Their acts are performed with full self-expression, yet without strut or intrusion of consciousness. Whatever comes from them is happily blended and organized into the entirety of life. Such should be our aim. We should seek to be born again, and not to remain where we were originally born.

V

In what has now been said there is a good deal of comfort for those who suffer the pains of self-consciousness, previously described. They need not seek a lower degree of self-consciousness, but only to distribute more wisely what they now possess. In fullness of consciousness they may well rejoice, recognizing its possession as a power. But they should take a larger unit for its exercise. In meeting a friend, for example, we are prone to think of ourselves, how we are speaking or poising our body. But suppose we transfer our consciousness to the subject of our talk, and allow ourselves a hearty interest in that. Leaving the details of speech and posture to mechanized past habits, we may turn all the force of our conscious attention on the fresh issues of the discussion. With these we may identify ourselves, and so experience the enlargement which new materials bring. When we were studying the intricacies of self- sacrifice, we found that the generous man is not so much the self- denier or even the self-forgetter, but rather he who is mindful of his larger self. He turns consciousness from his abstract and isolated self and fixes it upon his related and conjunct self. But that is a process which may go on everywhere. Our rule should be to withdraw attention from isolated minutiae, for which a glance is sufficient. Giving merely that glance, we may then leave them to themselves. Encouraging them to become mechanized, we should use these mechanized trains in the higher ranges of living. The cure for self-consciousness is not suppression, but the turning of it upon something more significant.

VI

Every habit, however, requires perpetual adjustment, or it may rule us instead of allowing us instead to rule through it. We do well to let alone our mechanized trains while they do not lead us into evil. So long as they run in the right direction, instincts are better than intentions. But repeatedly we need to study results,–and see if we are arriving at the goal where we would be. If not, then habit requires readjustment. From such negative control a habit should never be allowed to escape. This great world of ours does not stand still. Every moment its conditions are altering. Whatever action fits it now will be pretty sure to be a slight misfit next year. No one can be thoroughly good who is not a flexible person, capable of drawing back his trains, reexamining them, and bringing them into better adjustment to his purposes.

It is meaningless, then, to ask whether we should be intuitive and spontaneous, or considerate and deliberate. There is no such alternative. We need both dispositions. We should seek to attain a condition of swift spontaneity, of abounding freedom, of the absence of all restraint, and should not rest satisfied with the conditions in which we were born. But we must not suffer that even the new nature should be allowed to become altogether natural. It should be but the natural engine for spiritual ends, itself repeatedly scrutinized with a view to their better fulfillment.

VII

The doctrine of the three stages of conduct, elaborated in this chapter, explains some curious anomalies in the bestowal of praise, and at the same time receives from that doctrine farther elucidation. When is conduct praiseworthy? When may we fairly claim honor from our fellows and ourselves? There is a ready answer. Nothing is praiseworthy which is not the result of effort. I do not praise a lady for her beauty, I admire her. The athlete’s splendid body I envy, wishing that mine were like it. But I do not praise him. Or does the reader hesitate; and while acknowledging that admiration and envy may be our leading feelings here, think that a certain measure of praise is also due? It may be. Perhaps the lady has been kind enough by care to heighten her beauty. Perhaps those powerful muscles are partly the result of daily discipline. These persons, then, are not undeserving of praise, at least to the extent that they have used effort. Seeing a collection of china, I admire the china, but praise the collector. It is hard to obtain such pieces. Large expense is required, long training too, and constant watchfulness. Accordingly I am interested in more than the collection. I give praise to the owner. A learned man we admire, honor, envy, but also praise. His wisdom is the result of effort.

Plainly, then, praise and blame are attributable exclusively to spiritual beings. Nature is unfit for honor. We may admire her, may wish that our ways were like hers, and envy her great law-abiding calm. But it would be foolish to praise her, or even to blame when her volcanoes overwhelm our friends. We praise spirit only, conscious deeds. Where self-directed action forces its path to a worthy goal, we rightly praise the director.

Now, if all this is true, there seems often-times a strange unsuitableness in praise. We may well decline to receive it. To praise some of our good qualities, pretty fundamental ones too, often strikes us as insulting. You are asked a sudden question and put in a difficult strait for an answer. “Yes,” I say, “but you actually did tell the truth. I wish to congratulate you. You were successful and deserve much praise.” But who would feel comfortable under such eulogy? And why not? If telling the truth is a spiritual excellence and the result of effort, why should it not be praised? But there lies the trouble. I assumed that to be a truth-teller required strain on your part. In reality it would have required greater strain for falsehood. It might then seem that I should praise those who are not easily excellent, since I am forbidden to praise those who are. And something like this seems actually approved. If a boy on the street, who has been trained hardly to distinguish truth from lies, some day stumbles into a bit of truth, I may justly praise him. “Splendid fellow! No word of falsehood there!” But when I see the father of his country bearing his little hatchet, praise is unfit; for George Washington cannot tell a lie.

Absurd as this conclusion appears, I believe it states our soundest moral judgment; for praise never escapes an element of disparagement. It implies that the unexpected has happened. If I praise a man for learning, it is because I had supposed him ignorant; if for helping the unfortunate, I hint that I did not anticipate that he would regard any but himself. Wherever praise appears, we cannot evade the suggestion that excellence is a matter of surprise. And as nobody likes to be thought ill-adapted to excellence, praise may rightly be resented.

It is true, there is a group of cases where praise seems differently employed. We can praise those whom we recognize as high and lifted up. “Sing praises unto the Lord, sing praises,” the Psalmist says. And our hearts respond. We feel it altogether appropriate. We do not disparage God by daily praise. No, but the element of disparagement is still present, for we are really disparaging ourselves. That is the true significance of praise offered to the confessedly great. For them, the praise is inappropriate. But it is, nevertheless, appropriate that it should be offered by us little people who stand below and look up. Praising the wise man, I really declare my ignorance to be so great that I have difficulty in conceiving myself in his place. For me, it would require long years of forbidding work before I could attain to his wisdom. And even in the extreme form of this praise of superiors, substantially the same meaning holds. We praise God in order to abase ourselves. Him we cannot really praise. That we understand at the start. He is beyond commendation. Excellence covers him like a garment, and is not attained, like ours, by struggle through obstacles. Yet this difference between him and us we can only express by trying to imagine ourselves like him, and saying how difficult such excellence would then be. We have here, therefore, a sort of reversed praise, where the disparagement which praise always carries falls exclusively on the praiser. And such cases are by no means uncommon, cases in which there is at least a pretense on the praiser’s part of setting himself below the one praised. But praise usually proceeds down from above, and then, implicitly, we disparage him whom we profess to exalt.

Nor do I see how this is to be avoided; for praise belongs to goodness gained by effort, while excellence is not reached till effort ceases in second nature. To assert through praise that goodness is still a struggle is to set the good man back from our third stage to our second. In fact by the time he really reaches excellence praise has lost its fitness, goodness now being easier than badness, and no longer something difficult, unexpected, and demanding reward. For this reason those persons are usually most greedy of praise who have a rather low opinion of themselves. Being afraid that they are not remarkable, they are peculiarly delighted when people assure them that they are. Accordingly the greatest protection against vanity is pride. The proud man, assured of his powers, hears the little praisers and is amused. How much more he knows about it than they! Inner worth stops the greedy ear. When we have something to be vain about, we are seldom vain.

VIII

But if all this is true, why should praise be sweet? In candor most of us will own that there is little else so desired. When almost every other form of dependence is laid by, to our secret hearts the good words of neighbors are dear. And well they may be! Our pleasure testifies how closely we are knitted together. We cannot be satisfied with a separated consciousness, but demand that the consciousness of all shall respond to our own. A glorious infirmity then! And the peculiar sweetness which praise brings is grounded in the consciousness of our weakness. In certain regions of my life, it is true, goodness has become fairly natural; and there of course praise strikes me as ill-adjusted and distasteful. I do not like to have my manners praised, my honesty, or my diligence. But there are other tracts where I know I am still in the stage of conscious effort. In this extensive region, aware of my feebleness and hearing an inward call to greater heights, it will always be cheering to hear those about me say, “Well done!” Of course in saying this they will inevitably hint that I have not yet reached an end, and their praises will displease unless I too am ready to acknowledge my incompleteness. But when this is acknowledged, praise is welcome and invigorating. I suspect we deal in it too little. If imagination were more active, and we were more willing to enter sympathetically the inner life of our struggling and imperfect comrades, we should bestow it more liberally. Occasion is always at hand. None of us ever quite passes beyond the deliberate, conscious, and praise-deserving line. In some parts of our being we are farther advanced, and may there be experiencing the peace and assurance of a considerable second nature. But there too perpetual verification is necessary. And so many tracts remain unsubdued or capable of higher cultivation that throughout our lives, perhaps on into eternity, effort will still find room for work, and suitable praises may attend it.

REFERENCES ON THE THREE STAGES OF GOODNESS

James’s Psychology, ch. iv.

Bain’s Emotions and the Will, ch. ix.

Wundt’s Facts of the Moral Life, ch. iii.

Stephen’s Science of Ethics, ch. vii. Section iii.

Martineau’s Types of Ethical Theory, pt. ii. bk. i. ch. iii.

![[Buy at Amazon]](http://images.amazon.com/images/P/0766150887.01.MZZZZZZZ.jpg)